On February 26, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev, the then-leader of the Soviet Union, addressed a closed session of the 20th Communist Party Congress and denounced the cult of personality of his predecessor, Josef Stalin. Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” was a four-hour long condemnation of Stalin’s myriad abuses of power, a shocking and detailed indictment of the dictator’s crimes delivered just three years after his death.

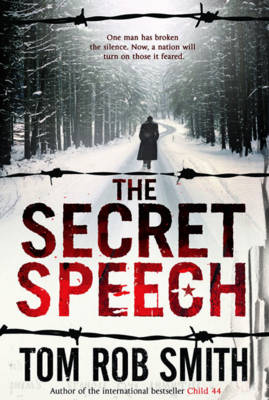

British author Tom Rob Smith’s new historical thriller The Secret Speech (Grand Central Publishing) traces the ripple effects of Khrushchev’s denunciation of the “pockmarked Caligula” (to use Boris Pasternak’s chilling description), and explores how those revelations profoundly altered the lives of both persecutors and persecuted in the totalitarian state Stalin had fashioned.

While Khrushchev tried to narrow the focus to Stalin and his depraved comrade Lavrenty Beria, the chief of secret police (and serial rapist of young girls) who was executed after Stalin’s death, there was broad complicity in the horrors of Stalinism, beginning with Communist Party elites. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people in the Soviet national security apparatus aided in the torture, abuse, summary execution, and unjust imprisonment of their fellow citizens. Some were willing accomplices in the purges and show trials, convinced that they were defending against subversion by enemies of the state. Others collaborated or informed out of fear or self-interest. The exposure of Stalinism’s systemic perversion of justice shattered the faith of true believers around the world (the American Communist Party was devastated by the revelations). They discovered that they been lied to for decades about the “necessary evil” of Stalin’s repression—it served not to advance scientific socialism, but to consolidate the power of a paranoid tyrant.

Shocking the system

The Secret Speech is set just after Khrushchev’s shock to the system, and Smith dramatizes its effects through the story of Leo Demidov, a hero of the Great Patriotic War and former MGB officer (and the protagonist of Smith’s bestselling debut novel, Child 44). As the book opens, Demidov is working as a homicide detective in Moscow, a job that brings him into contact with all levels of Soviet society and lets us watch as word of Khrushchev’s revelations quickly spreads. (The conceit—a skeptical Russian insider/outsider with police powers—is a familiar one: Martin Cruz Smith’s character Arkady Renko, also a detective, memorably explored the contradictions of Soviet life in Gorky Park and a follow-on series of thrillers.)

Leo hopes that his new position will help him make amends for his own culpability in the abuses of the past. He and his wife Raisa have adopted sisters, Zoya and Elena, in part because Leo failed to stop the murder of their parents by one of his MGB subordinates. On his self-chosen path to redemption, Leo discovers that some victims are not ready to forgive. Fraera, a woman Leo had helped wrongly condemn to the Gulag along with her husband as enemies of the state for their religious activities, has returned to Moscow, joined the vory v zakone (“thieves in law”), (the tattooed Russian mafia so vividly depicted in director David Cronenberg’s movie Eastern Promises), and has targeted Demidov for vengeance. To protect his family, Leo must journey to the Kolyma region (the Gulag’s “pole of cold and cruelty” according to Alexander Solzhenitsyn) and attempt, against long odds, to liberate Fraera’s still-imprisoned husband, Lazar.

Smith paints a vivid portrait of the bleak, unforgiving world of the forced labor camps in Siberia. Leo’s scheme to infiltrate Gulag 57 and free Lazar goes awry when his true identify is discovered; only a camp uprising triggered by news of Khrushchev’s speech saves Demidov from immediate reprisal at the hands of the prisoners. In one of the novel’s most arresting scenes, Gulag 57’s commander Zhores Sinyavksy faces a makeshift court convened to pass judgment on his treatment of the imprisoned. Sinyavksy pleads his case in vain—he receives a just, but not merciful, sentence from the convicts before Red Army tanks end their brief moment of freedom.

In seeking to craft a suspenseful page-turner, Smith relies on too many unbelievable twists and turns to advance the narrative of The Secret Speech. A final plot contrivance that brings Leo and Raisa to Budapest to witness the Hungarian revolution in the fall of 1956 is particularly awkward. Smith invents a conspiracy—Kremlin hardliners sending agent provocateurs to Hungary to spark the uprising and justify a crackdown by a resurgent Soviet military—that doesn’t pass historical muster. In fact, the Hungarian revolt represented an authentic expression of discontent by a coalition of intellectuals, students, and workers. It was a development that took the Soviet hierarchy by surprise. The broad popular support for the uprising and the participation of young educated Hungarians posed an existential challenge to Marxist-Leninist ideology which had maintained that such classless solidarity could only develop under Communism.

Budapest 1956 also caught the West off guard. Tim Weiner notes in Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, the American intelligence establishment was clueless, without a network or agents on the ground: “During the two-week life of the Hungarian revolution, the agency knew no more than what it read in the newspapers…Had the White House agreed to send weapons, the agency would have had no clue where to send them.” American involvement was limited to misleading Radio Free Europe broadcasts that raised false hopes of Western intervention.

Despite its over-plotting, The Secret Speech is compelling in its depiction of the first halting steps away from Communism. Leo’s difficult journey from dedicated secret policeman to clear-eyed survivor mirrors in personal terms the beginning of that transformation. The moral reckoning isn’t easy. Some of his MGB colleagues cannot live with their guilt. Careerists and opportunists have less difficulty adjusting to the new order. Others in the bureaucracy calculate the risks of embracing reform should de-Stalinization prove temporary and the ground under them shift once again.

Stalin’s legacy?

The Khrushchev Thaw proved to be a partial one. The Kremlin maintained Stalinist security measures throughout the Soviet empire for another three decades. Indeed, nearly twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the former KGB agent who controls the Russian government has shown little appetite for any “truth and reconciliation” process that might comprehensively address the horrors of Stalinism. Some Russians still long for the days of Stalin. In a disturbing sign of this revisionist nostalgia, Stalin was voted the third most popular Russian historical figure in a poll by the Rossiya state television channel in December 2008.

Historical myopia isn’t confined to the Russians. In his Los Angeles Times review of Smith’s novel, Michael Harris compared Stalinist collaborators with Americans today, noting: “…with hardly a repercussion to be afraid of, those who opposed Bush-era policies are acquitting themselves no better, while hard-liners such as Dick Cheney continue to warn that too much concern for civil rights will risk another 9/11.” Harris failed, however, to specify the heroic acts of resistance that he thought Code Pink and other liberal-left opposition groups should have employed during the Bush years. Yes, it’s hard to believe that even someone suffering from such a clear case of Bush Derangement Syndrome could compare Stalin’s Soviet Union to George W. Bush’s America, but, as baseball great Casey Stengel used to say, you can look it up.

Copyright © 2009 Jefferson Flanders

All rights reserved

Leave a Reply