This piece appeared on History News Network as: Review of Eva Dillon’s “Spies in the Family: An American Spymaster, His Russian Crown Jewel, and the Friendship That Helped End the Cold War”

We have learned since the end of the Cold War that the West had well-placed spies in the Kremlin, and that those double agents provided timely intelligence about Soviet aims and intentions. It’s impossible to gauge their full impact in hastening the fall of the Communist regime, but it’s clear that these inside sources helped policymakers in London, Paris, and Washington in assessing the thinking of the Politburo and other Soviet leaders.

A new memoir/history by Eva Dillon, Spies in the Family, offers a fascinating and deeply sympathetic account of perhaps the most important of the Kremlin spies, Dmitri Polyakov, code name TOPHAT, who was the third major GRU (military intelligence) officer to pass vital information to the CIA. All three were discovered. Polyakov lasted the longest; the other two—Pyotr Popov and Oleg Penkovsky—were betrayed, it is believed, by British mole George Blake (who is in his 90s, living in exile in Moscow).

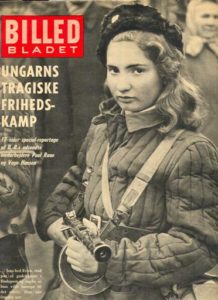

Popov, a lieutenant colonel in the GRU, was the CIA’s first in-place source in the Soviet hierarchy. He approached an American diplomat in Vienna in 1953 and offered his services as a spy, motivated in part by anger over the harsh treatment of Russian peasants, including his own family. Popov passed along information about Soviet nuclear submarines and missile technology and alerted the CIA that the GRU had classified technical information about the U-2 spy plane. He was exposed and executed in 1960.

Penkovsky is perhaps the best known of Soviet double agents. He played a role in both the Berlin Crisis in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year. Penkovsky passed technical information about the Soviet nuclear missiles sent to Cuba that helped steer the Kennedy Administration away from a military response. As the CIA has noted: “Because of Penkovksy, Kennedy knew that he had three days before the Soviet missiles were fully functional to negotiate a diplomatic solution. For this reason, Penkovsky is credited with altering the course of the Cold War.” Also betrayed, Penkovsky was tried publicly and executed in May of 1963.

Eva Dillon’s subject, Dmitri Polyakov, considered himself a Russian patriot who in practice subscribed to the 17th century dramatist Pierre Corneille’s belief that “treachery is noble when aimed at tyranny.” Dismayed by Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s bellicosity, he began spying for the FBI and CIA in 1961 and avoided exposure until 1988. (Popov lasted six years; Penkovsky, only two). Polyakov achieved the rank of general, becoming the West’s highest-placed spy. Eva Dillon’s father, Paul, a CIA officer and an Irish Catholic marine from Boston, was one of Polyakov’s handlers and developed a strong bond with him.

As Polyakov rose in the GRU, he “had access to the highest level of Soviet war planning, strategy, and military philosophy. He knew the specifics of worldwide GRU operations. He knew the identities of GRU agents and their modi operandi.” His courage can’t be underestimated. To spy in the Soviet Union, a totalitarian society, required nerves of steel, with the danger of exposure real and constant. In Spies in the Family, Dillon captures this tension, and the moral dilemma Polyakov faced—he felt compelled to continue spying, even as he knew it placed his family (and their future) at grave risk. Dillon interviewed Polyakov’s son, whose career as a diplomat ended after his father’s arrest, and who moved to the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union, his career prospects tainted.

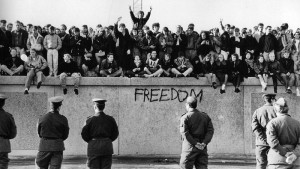

In the end, Polyakov was compromised by the CIA’s Aldrich Ames, a mole who betrayed numerous Western agents. When arrested, Polyakov told his interrogators that he saw himself as a “social democrat,” one who saw the Scandinavian countries as a model for Russia. Despite Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms, Polyakov’s justification for his spying fell on deaf ears. Earlier, Polykov had turned down an offer of asylum from the CIA, explaining, “I am not doing this for you. I am doing this for my country. I was born a Russian, and I will die a Russian.” His words came true: he was tried, convicted, and executed, all in secret.

Polyakov must have had few illusions about how his countrymen would view him, even those who welcomed the fall of the regime. And yet he persisted, driven by his own sense of duty and an old-fashioned patriotism. As James Woolsey of the CIA later noted: “What General Polyakov did for the West didn’t just help us win the Cold War, it kept the Cold War from becoming hot. Polyakov’s role was invaluable, and it was one that he played until the end—in his own words—for his country.”

As U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller and several Congressional committees investigate Russian attempts to influence the 2016 presidential election, it’s logical to ask what the CIA and/or MI6 might know from inside sources in Moscow. Are there “social democrats” in Vladimir Putin’s inner circle who reject his strongman approach and regard cooperating with the West as a patriotic duty? These sources might offer concrete information about the extent of Russian meddling, and possible collusion with Trump associates, well beyond the gossip, rumors, and conjecture of the dossier compiled by ex-MI6 officer Christopher Steele.

Another intriguing question: can the current Administration be trusted with the names of any highly-placed Russians passing information? The fear of a leak, or inadvertent disclosure by an erratic President not known for his self-control or caution, is real. The fate of some of Putin’s critics (journalists murdered; opposition leaders assassinated; former cronies dying under mysterious circumstances) suggests the potentially dire consequences of exposure (no less, perhaps, than those faced by General Polyakov.) Putin is, after all, a creature of the KGB.

If history is any guide, there are covert Western intelligence sources in Moscow. (If there are not, then the CIA is not doing its job.) How to shield them, and yet fully explore what they can tell us about the extent of Russian hacking and disinformation campaigns, is a pressing challenge for the leaders of the intelligence community. Before too long we may learn what they know, and what it means for the health of our democratic institutions and the rule of law in our country.

Jefferson Flanders is an independent journalist and author. His trilogy of novels, The First Trumpet, is set during the early Cold War.

Copyright © 2017 by Jefferson Flanders