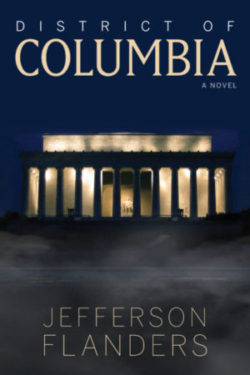

NOW AVAILABLE:

District of Columbia, the latest novel from Jefferson Flanders

“A remarkable tale of political maturity, and its steep price.” – Kirkus Reviews

“In Jefferson Flanders’ compelling historical novel, the ideals of a privileged young man of the East Coast establishment and his like-minded friends are severely tested by the wrenching changes of the 1960s and ’70s that would transform America.” – BlueInk Review

ABOUT THE NOVEL:

Washington, D.C. January 1961. Dillon Randolph, a young State Department official, caught up in the heady days of President Jack Kennedy’s new administration, resolves to help make real the promises of the New Frontier. But the deepening Vietnam conflict causes Dillon to question not only the direction of the war, but also his most fundamental assumptions about his professional and personal life.

District of Columbia captures the turmoil of the 1960s at home and abroad. It tells a haunting and profound tale of lost innocence, of the arrogance of power, of the brutality and tragedy of war, and of lives forever transformed.

FROM THE AUTHOR:

District of Columbia proved to be a hard book to write. That’s meant as an observation, not a complaint.

The novel is largely set in the 1960s, a particularly difficult time for our country, a divisive time filled with painful memories, of assassinations, of civil strife, and of an unpopular and terribly-destructive war. Having lived through the period, it wasn’t easy to revisit those times. I had to grapple with my own conflicted feelings about the conflict in Vietnam, and where it fit into the Cold War.

District of Columbia began as a sequel to An Interlude in Berlin, and initially, I intended for the book to be a historical thriller. But as I told the story I felt compelled to tell, it became more of a political novel. That may not sit well with some of my readers, and I’m prepared for some negative responses (and reviews). All I can say in my defense is that sometimes as a writer your imagination takes you in an unexpected direction. I’ve learned not to resist when that happens.

My protagonist, a young diplomat, experiences many of the highs and lows of a decade of turmoil. Dillon Randolph is at heart a traditionalist; he is unprepared for the social and cultural sea change he confronts. The challenges in his life mirror what was happening for many of his generation.